Tikendrajit : The Lion of Manipur

- Part 2 -

Dr. Lokendra Arambam *

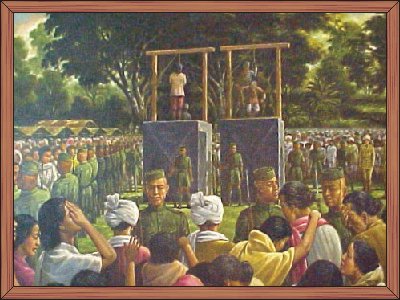

Yuvaraj Tikendrajit and General Thangal on the Gallows.

Warning: These images CANNOT be reproduced in any form or size without written permission from the RKCS Gallery

Tikendrajit though he inherited the best traditions of royalty in the continuity of the concepts of the golden country in the worldview of kingship, was not personally ambitious for power and exercise of power. He was simply raised in the ranks of post-holders within the families of the royal household, that he was given the post of supervisor of the affairs of the police, which was termed Kotwal, a sort of jurisdiction over the cases of crimes and keeping of the peace.

Yet as a prince warrior always ready to extend his hand over military affairs, he joined the expeditions of the Manipur army in its support to the high officials of the British Empire to gain experience in war and statecraft where he became associated with the experienced elder statesmen and warriors like Thangal General, General Balram and other distinguished veterans of the Manipur army.

His association with Thangal major were evident in the latter period of MaharajahChandrakirti's life, when he became more and more concerned with the rapid acceleration of the powers of the British Empire amongst the princely families in India. The promises of the British crown no longer to annex territories in South Asia were suddenly overturned when the opportunity arose, and the post-mutiny overtures of the British to secure more effective control over the tribal inhabited territories surrounding Manipur, and their hunger for bigger control in the affairs of Burma after the accession of lower Burma in the second Anglo-Burmese wars of 1852 became critical matters of geopolitics of the time.

Though Manipur was an Asiatic State in alliance with the British Empire, the Manipur monarchy extended full hearted support to the extension of the British imperial geography in the north and the south of Manipur. The settlement of the boundaries of the Manipur territories in the north which became contiguous to the British territories which came existence in the 1860s created irritations in the relationship between the two entities.

The Manipur monarchy was suspicious of the land hunger of the imperial power and their meticulous insistence on sheer graphic knowledge of the hills, mountains and rivers, their hunger of conquest of routes, villages and ethnic settlements to ensure security and safety to the future healthof the empire, their postures and manners of their military officials towards the native aristocracy of Manipur became indeed sour notes in the relationship between the powerful empire and their officials with the elder warrior statesmen of Manipur.

Though in the later stages of Maharajah Chandrakirti's rule in 1870s, most of the warrior tribes like the Angamis and the Lushai were being pacified through force of arms as well as renewed pledges of trust and ritual. Even though in 1874, there was a historic moment of British and Manipur friendship through the famous meeting with Lord Northbrook by Maharajah Chandrakirti over a yacht on the Barak River at Cachar, the latter days were not healthy days for Manipur-British relations.

A political agent like James Johnstone could utilize the service of the Manipur Army for his pacification of the Angamis in 1878, as well as help in the final conquest of Burma in 1885, it could be noticed that the martial energy of the Manipur army and the service of men like Thangal, Balram and Col. Shamu Singh were utilised to suppress dissident tribal communities, clear jungles and routes for the imperial army for the ultimate conquest of Burma, and the last few years in the life of Maharajah Chandrakirti Singh, the services of the native army were maximally utilized for the sheer cause of the British Empire without any substantial returns for the cause of the state.

The enormous tribal migrations from Burma to Manipur in latter periods of the 19th century were sympathetically settled in the southern and south western hills of Manipur. The suppression of the Angamis in 1878 by the Manipur army by Major Thangal and Major Shamu were accompanied by the eldest son of Maharajah Chandrakirti, Surchandra Singh, theYubaraj of the state. Tikendrajit himself participated in this expedition.

James Johnstone was no admirer of the young talent in the princes of the royal family. His concerns for British subjects in Manipur at the expense of the native sons of the soil were matters of cultural and demographic related tensions and the silent activities of companies like the Bombay-Burma Trading Co-operation in their extensive exploitation of timber and other forest resources of Burma, and their deals for connectivity and profit making concerns became matters of deep suspicion by the patriotic native elite. They encouraged surveillance over the activities of these British subjects.

The sense of cultural difference developing under the practical processes of empire making, the frictions in boundary issues and difference of British Indian subjects, their culture and economic practices with those of the natives were conflictual in the freshly expanding networks in human movements, migrations and flows of goods and services, which the traditional Manipur nobility experienced as irritable and disturbing of their cherished equilibrium of life.

The quantum of Manipur activity in connection with movement of soldiers and suppression of tribal disturbances in Manipur's eastern frontiers which were necessitated by British requests for help in arms and logistics, which were not considered difficult in the heydays of Manipur independence were felt to be wearisome and suspicious in the latter periods of Maharajah Chadrakirti's life.

Rebellions amidst clan aspirants for the Manipur throne were too not infrequent, and immediately after the death of the king in 1886, his eldest son Surchandra had to suppress the rising of Sana Borachaoba, and Tikendrajit took a prominent part in suppressing the rebellion. Tikendrajit's post in the new hierarchy rose, and he was made the Senapati or Commander of the army when Surchandra reigned (1886–90).

Contemporary historians of Manipur did not ponder the reality of the British occupation of the entire sub-continent of Burma through Manipur support in 1885 and its impact on the nature of British relations with native states in South Asia. It must be mentioned that the post 1885 British conquest of Burma and the fall of the Konbaung dynasty had its impact on the defeated psyche of the Burmese patriots and there were furious resistances in upper Burma for nearly four years, and the British took harsh measures to quell them.

The Burmese insurgency after the annexation of Burma lasted till 1890, and the British took severe measures like massacres, hangings of leaders of the rebellion in the roadsides, and women and children were not spared. The insurgents too murdered Scottish doctors, the hanging of the rebels on the roadsides did not receive international attention, but it became a scandal at the end of Anglo-Manipur war through the sacrifice of Tikendrajit and his freedom fighters.

A British captain wrote a poem on the hangings in post-annexation Burma and its message was very clear.

Under a spreading mango tree

A Burmese Chieftain stands

His hour has come; a captive he

Within the conqueror's hands

And they fasten around his sturdy neck

A noose of hempen strands.

Under a spreading mango tree

A lifeless body swings

Though bound its limbs a soul is free

And spreads on joyful wings

To solve the perplexing mysteries of

Ten Thousand hidden things.

Under a spreading mango tree

A Buddhist chapel stands,

Where children pray on bended knee.

Amidst the simmering sands.

That the seeds of Western culture may

Take root in eastern lands!

(Quoted by MaungHtin Aung, 1967).

Conflict of Symbols in the Anglo-Manipur War 1891

Manipuri scholars, following the attitude of their British masters in their analysis of the character and behaviour of the Manipur princes in their struggle for power of the throne, often spoke of the hatred and spite amongst the aspirants of the throne. They write about the animosity, hatred and factional disputes between the sons of Maharajah Chandrakirti and point to Tikendrajit as being the mastermind of the palace revolution of 1890, the coup against the eldest son Surchandra's occupation of the throne, and thereby leading to the intervention of the British on the issue of succession to the throne.

Not much of studies are done by Manipuri scholars on the issue of what it is to occupy the throne, and how the throne represented a sacred energy bequeathed by the ancients which empower the occupant to serve the basic unity of the cosmos and the earth, and to effect the regulation of the course of the seasons to provide welfare and equilibrium to the citizens, that the court and palace of the king should represent an exemplary centre, a model of the heavenly abode of human ancestors who provided the life and continuity of the race, and the vivacity and joy of living.

The throne was indeed a sacred power which the incumbent received through a complex ritual of coronation whereby the spirits of the ancestors empowered the occupant the right to effect force to govern the state and model the polity towards a spiritual attainment which was sacred, sanct and pure. The ancient capital Kangla was therefore a sacred ritual centre which should never be contaminated by profane human acts, and attack on the sacred space should be punished by capital punishment.

By tradition of the absence of the law of primogeniture, the princes had a moral and spiritual right to succession, but the wishes of the elders, the women of the court, and the desire of the populace would be important factors to succession. But the changes of perceptions and precepts in association of new values that penetrated the realm in the wake of a new world religion and practical pragmatic influences of the secular western ideas would have had a dilutic effect on matters of politics and exercise of power later in history.

The conflict amongst the brothers and cousins amidst the sons of Chandrakirti no doubt has poignancy and thrust in the scramble for power, but at the same time we have to be aware of the contemporary experiences in the history of the Burmese polity in the 18th and 19th centuries which had similar refrains in those of Manipur, who shared valuable culture and traditions of the courts. We must be aware of the fratricidal conflicts and massacres in the Konbaung dynasty amidst the successors to Alaung Zeya (Alompra by Manipuris, 1750–60), and Bodaw Paya (1782–1819), who was the fourth son of Alaung Zeya effected a murder of some eighty three princes and princesses in 1789.

This sort of fratricidal blood-letting was also effected during the reign of Thibaw, the last of the Konbaung dynasty (1875–85), who massacred some seventy to eighty brothers and kinsmen in Mandalay in 1878, which was known as the Massacre of the Kins. In Burmese tradition it was in fact a purging of the realm according to custom, and the body of the king was homologous with the body of the polity. This was so in Manipur too. Manipur had an autonomous, independent attitude to kingship and occupation of the throne according to ancient beliefs and traditions.

The British authorities had a mundane, earthy notion of holding of power as a source of control over people and resources, and they claimed the right to intervene in all aspects of succession to kingships all over India, thereby gradually depriving political authorities of the princes the exercise of their own sovereignty. For Manipur it was a challenge to their civilizational symbols and beliefs. The midnight attack in the capital by Quinton and his co-hosts was a severe trampling upon the sacred space of the Kangla, the sacred navel of the universe of the Meitei. 'Heads of white bodies shall roll in front of the Kangla Uttra' was a prediction of the soothsayers.

To be continued....

* Dr. Lokendra Arambam wrote this article which was published at Imphal Times

This article was posted on 21 August, 2018 .

* Comments posted by users in this discussion thread and other parts of this site are opinions of the individuals posting them (whose user ID is displayed alongside) and not the views of e-pao.net. We strongly recommend that users exercise responsibility, sensitivity and caution over language while writing your opinions which will be seen and read by other users. Please read a complete Guideline on using comments on this website.