Culture of Kangleipak

- Part 3 -

Uttam Mangang *

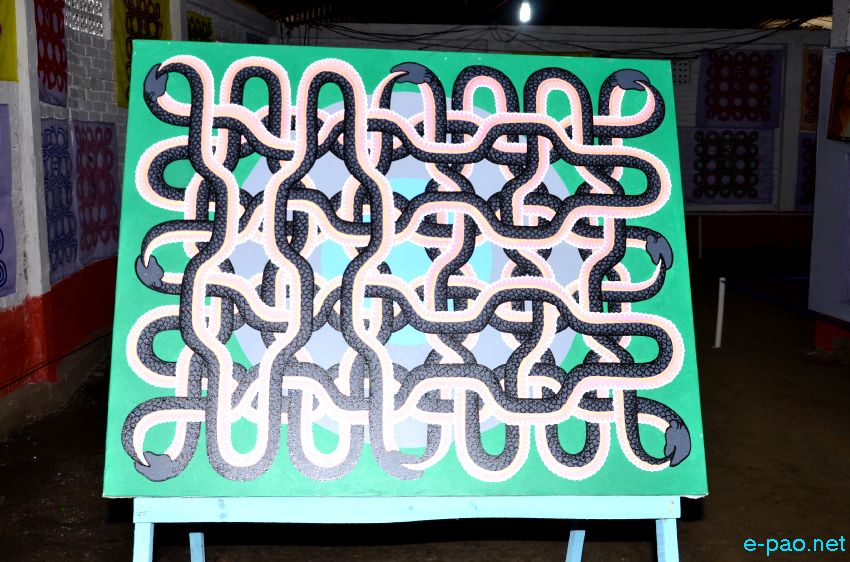

'Malem Paphal Art Exhibition Manipur' at Iboyaima Shumang Leela Shanglen in May 2015 :: Pix - Shankar Khangembam

It will be wrong to conclude that as both the hill people and inhabitants of the valley were animists and as such they are not advanced and an enlightened people. A huge divide emerged between the hill and valley people after the former embraced Christianity and the latter Hinduism who were brothers and sisters in the past. Christianity was introduced by William Pettigrew and he was helped by Angom Purum Singha of Phayeng, a Meetei. At present Christianity is the major religion in the hills of Manipur.

It is mentioned by H.W.O. Slevenson in his work "The Hill Peoples of Burma": "The Phenomenon of detribalization appeared everywhere, men became fish out of water, unable to indentify themselves with either the Western people whose culture they aped or their forefathers". Western culture came to be mixed with Eastern culture. Still a belief, based on Kanglei puya, prevails where it is said that Nongpok Thong (Eastern Gate) will be opened and Nongchup Thong (Western Gate) will be shut. This is known locally as Nongpok Cheingkhei Lalumpa.

Decadence of our culture :

A preservation of our culture and identity is very important. In a place where there is a crisis of identity, production, reproducation, tradition and tradition-making suffer. A glaring example is the system of

labour which was mentioned in 'Loyumpa Sinyen' and introduced by our king Loyumpa in 1078. According to this a classless society oriented towards production was established. A form of division of labour existed in Kangleipak.

The following people were assigned to provide these items - Kakching supplied iron, Leimaram - bamboo products such as baskets, winnower etc., Khurkhul - silk, Sekmai - liquor, Andro- pots, Ningen - salt etc. The Thangjams were skilled in bringing out products of smithy; the Sanjetsabams were assigned with producing combs only. The Tensubams had the duty of producing bows and arrows etc. A prosperous society was present when the different groups of family, having their distinct family names, performed their duties according to the system of 'sinyen'. 'Loyumpa Sinyen' was like the Magna Carta – a written constitution of British administration.

It laid down certain rules and systems on customs, administration, labour and economy. After the advent of Hinduism, during the reign of King Pamheiba in 1709, a mixed form of faith came to be followed by the people of Kangleipak. It destroyed our original concepts of religion, custom and culture. The introduction of Hinduism posed as a hurdle in the indigenous process of production and formation of a well-settled nation. A form of human exploitation came into being. Caste system, under which the practices of untouchabity, hierarchy, persists became a part of our social system. Patriarchal system became a reality. The new concept of untouchabity served as a means to tear apart the hill people away from the people of the valley who lived together with trust and love.

Hinduism brought about a disruption in our original faith and way of dignity of labour. Accounts about 'sati' like those of 'Sati Khongnang', 'Meikibi Khongnang' etc emerged. They are found mentioned in Cheitharol Kumpapa – pages: 85, 94, 96 and 98. Some families who maintained piggery and poultry and served as skilled artisans came to be classed as 'Khutnaiba' or 'loi' and of a lower social class. For example, the Thangjams came to be known as workers belonging to a lower social class.

People started talking of shoemakers, washerman, barbers and those who reared 'Leima til' (mulberry -eating silk worms) as of a lower clan and 'loi'. These social outcasts moved and settled at Khurukhul and Sekmai etc. Out of this the use of home-grown cotton came to a close; outside influence and half-baked customs started coming to this place. The use of traditional looms became insignificant. It someone keeps pigs and poultry he or she was sent to exile, fined and harsh punishment was meted out. Brahmins and those who belong to the royal lineage (R.K.s) were forbidden to till land. Those who cultivated the Hindu way of singing and beating drums (pung) were revered and looked at with respect.

The traditional concept of 'Kaplak leikhom tieba' or being engaged in manual labour which was once practised by our able-bodied forefathers came to be replaced by the Hindu way of life. The Kangleis started looking for an easy way of earning and living just as a sleeping lion does; culture does not play a main role. In the past a courageous warrior was awarded according to his degree of bravery by the king.

In the past a warrior who could destroy the frontal portion of massed formation of enemy soldiers was awarded by the king with a token - Ningthou Phi Tajin Chatpa, one who bring disarry in the middle portion - Ningthou Phi Wanphak Phurit; and one who was able to totally destroy an entire enemy formation - Meibul Hajao. The last warrior had the honour of being greeted with rows of torches starting from his gate upto the royal palace. A warrior who had the courage of taking prisoner an enemy general or a king alive was awarded by being offered a lady out of the king's harem.

After the advent of Hinduism this practice was replaced by awarding only those Brahmins who were given the credit of bringing a battle to glory through their rituals. Even during the time of king Bheigyachandra Brahmins were chosen as generals. This was not accepted by the local warriors. It contributed to further defeats. This was a dampener to the skill and courage of Kanglei warriors. Our forefathers did not have the habit of accepting undeserved gifts and goods; they knew their own worth and tried to lead a way of life which was based on self-help and work.

As an example, the dignity of labour is shown by Khamba (an epic hero) when he refuses goods given to him freely and instead worked for them by looking after a wild bull. Our courageous warriors began to act like a sleeping lion. Once we took pride in truth and no one tried to do anything that will bring disgrace to society. The level of culture was high because of the presence of dignity of labour. In our present social arena work culture is absent with the disappearance of dignity of labour. We want to become suddenly rich through easy and unethical means. We have become choosy in our choice of work or labour; there is a false sense of pride, a prevalence of indiscipline and discourtesy, an unwillingness to look after and discipline our children at home.

There is no longer the institution of 'pakhang phal' and 'leisa pha'; the degradation of community – based activities, taking more interest in foreign language than in our mother tongue, putting more faith on the outside social culture, taking leisure for nothing, being addicted to external pomp, enjoying festivals every month, spending more on religious ceremonies and community feasts have contributed to the creation of a 'consumer society'. We have become parasites. There was a social mixture where hill people produced cotton and the valley people contributed with clothes and grain; that contact and love is now slowly lost.

As mentioned in the Emperial gazetter of India (1909), Kangleipak was not second to China in the production of silk; today we are at the bottom because of our disregard of work culture. 'Leisemlon, (the theory of creation of earth) says that earth was created by Lainingthou using the seven threads of silk in the form of a 'paphal'. The National Archives, New Delhi, 1904. Simla Records, gives this information that the production of silk was done by a marginalised group of Kangleis known as 'lois'. The Political Agent gave the estimate that around 640 kg of silk was produced annually and it was consumed by the local population.

The Kanglei cocoon was bought by the Burmese, with high desire, without haggling on its price because it was of a high quality. As keeping silk-worms was associated with the lower social group (loi), this industry could not make a progress. If a girl belonging to a Thangjam is to marry into a family of Samjetsabam, the tradition was to enquire whether there was any incestnal situation; this was replaced by looking into whether the concerned family was of the 'loi' group or they were manual workers. Thus, a form of branding materialised where someone was not accepted on the basis of social status, tabooed families etc. The expression 'jat taba' or lowering of social status became a part of our society.

In our past social system, a Meetei could act as a Brahmin as regards rituals, or as a 'piba maiba', a local healer; he could go to fight on a battlefield as a Kshetriya; and he could work as a Sudra, Veishya when it came to manual work. There was no 'caste system' and social stratification. Even when the physical environment is good a society can not make a progress if the cultural environment is destructive. It is natural that the poor will suffer more when the organised sector puts a powerful social pressure on the unorganised sector.

Once our forefathers gave the advice that we should grow and produce to be self reliant. Nowadays people want to get everything without working for them. Such manual works done by a barber, washerman, shoemaker etc. professions engaged in only by outsiders, could have been done by the people of Kangleipak. We remain unaware of everything and live a life of unqualified satiety. If such a situation persists we may not be able to maintain the territorial integrity of Kangleipak. Scholars are of the opinion that total revolution comes out of cultural revolution.

We may not be able to compete on the international level as market is concerned; there is a need to establish agro-based ancillary industries so that they may help in the future establishment of heavy industries. We are to be entrepreneurs for this. We should follow the wisdom provided by our folk tales and fables like Kabui Keioiba, Houdong Lamboiba, Urit Napangbi etc. Let us not forget the lesson from such a local game played by children – Miyan Khomdon Meiroubi and do our best to embrace tightly our cultural heritage.

A cultural revolution is to be revived as expounded by scholars. This is to be done legally. We are not to forget that 'Unity through Culture' includes both cultural integration and emotional integration. Socio-economic factors, political factors, cultural factors etc. are parts of the idea of 'Unity through Culture'. A nation can never rise up where there are indisciple and a culture without morality.

Conclusion:

At present we have become used to listening, seeing and looking at, eating and consuming things that are physically and morally damaging. The reasons for them are due to ignoring the cultural wealth of our forefathers, a negligence of our elders, forgetting how to act with discipline, a disbelief in the original religious faith etc. We lack conviction and integrity when we practise the norms of a religion. We are neither a Hindu or a Christian to the core. Besides them, there are socio-economic factors, political factors etc.

If we follow truth, non-violence and a deep belief in God we will never commit killings and murders. Such actions are never encouraged by any religion. We may not be sudden victims of our misdeeds, but we may face untold sufferings in the future. Therefore, we are to be merciful, have the strength to live together, helping one another and having a conscience. These divine principles are worth remembering. Let us work together so that the dark historical past may not repeat.

Concluded...

* Uttam Mangang wrote this article for Hueiyen Lanpao

The writer is Secretary General, People's Action For New Development Step

This article was posted on September 29, 2015.

* Comments posted by users in this discussion thread and other parts of this site are opinions of the individuals posting them (whose user ID is displayed alongside) and not the views of e-pao.net. We strongly recommend that users exercise responsibility, sensitivity and caution over language while writing your opinions which will be seen and read by other users. Please read a complete Guideline on using comments on this website.